57

The New Criterion

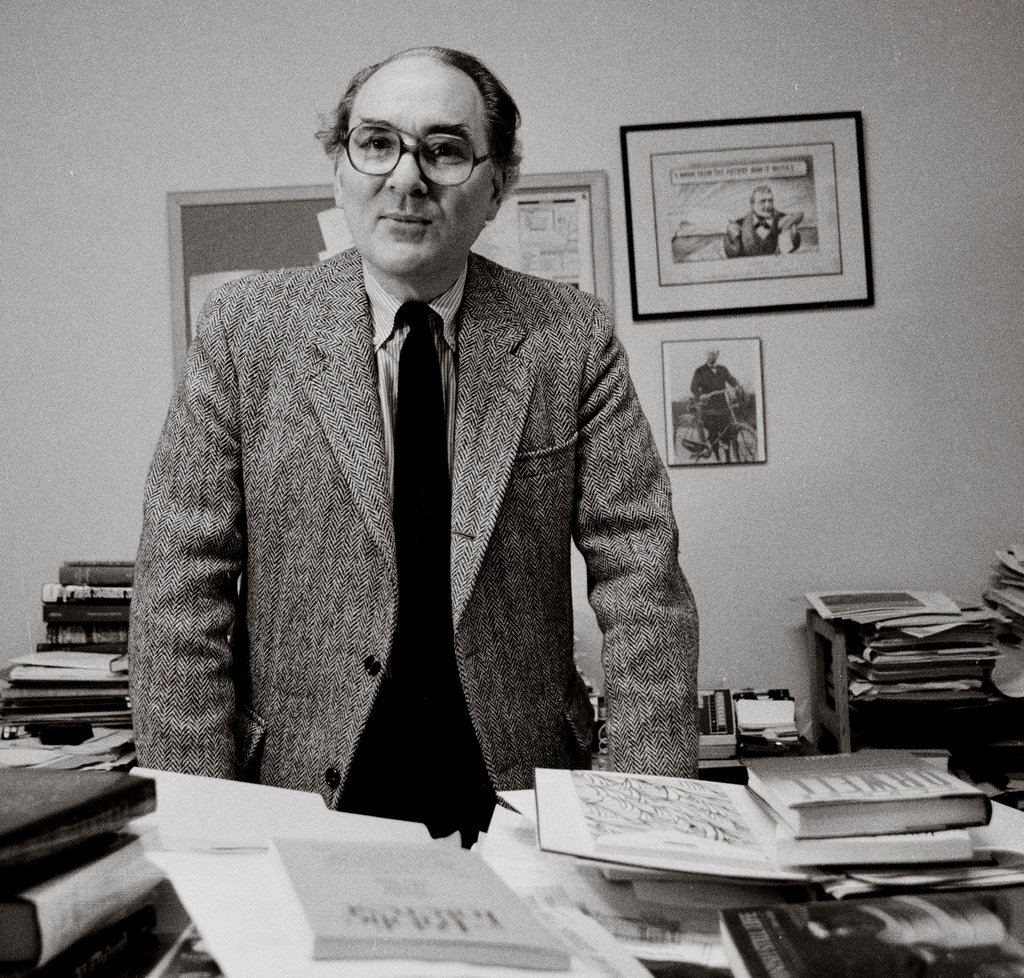

Author: Hilton Kramer

Year: 1982 Edit Add

Book: Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism

The New Criterion

Author: Hilton KramerYear: 1982 Edit Add

Book: Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism

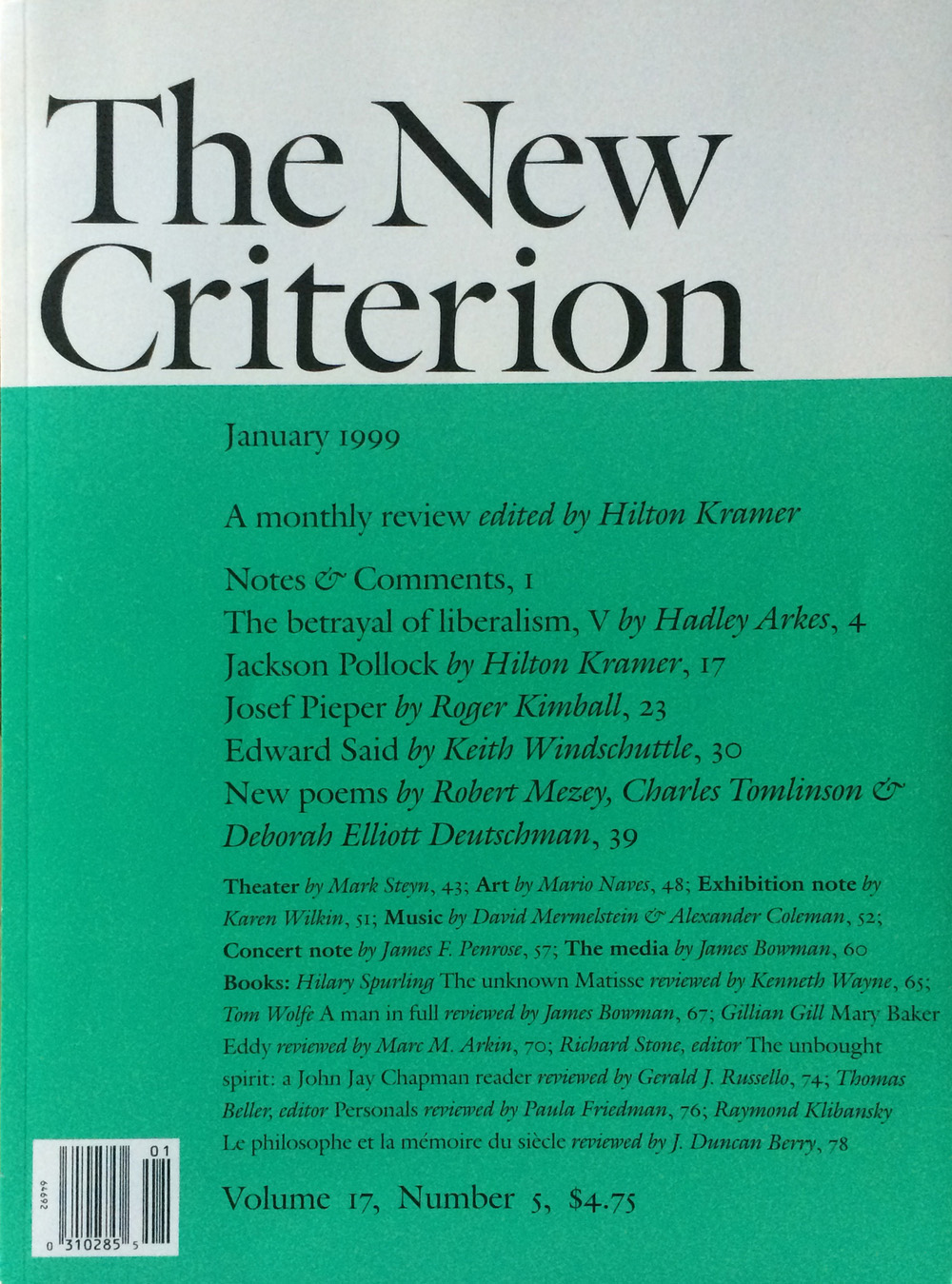

These positions -- antimodern, propostmodern -- then find their opposite number and structural inversion in a group of counterstatements whose aim is to discredit the shoddiness and irresponsibility of the postmodern in general by way of a reaffirmation of the authentic impulse of a high-modernist tradition still considered to be alive and vital. Hilton Kramer's twin manifestos in the inaugural issue of his journal, The New Criterion, articulate these views with force, contrasting the moral responsibility of the "masterpieces" and monuments of classical modernism with the fundamental irresponsibility and superficiality of a Postmodernism associated with camp and the "facetiousness" of which Wolfe's style is a ripe and obvious example.

What is more paradoxical is that politically Wolfe and Kramer have much in common; and there would seem to be a certain inconsistency in the way in which Kramer must seek to eradicate from the "high seriousness" of the classics of the modern their fundamentally anti-middleclass stance and the protopolitical passion which informs the repudiation, by the great modernists, of Victorian taboos and family life, of commodification, and of the increasing asphyxiation of a desacralizing capitalism, from Ibsen to Lawrence, from Van Gogh to Jackson Pollack. Kramer's ingenious attempt to assimilate this ostensibly antibourgeois stance of the great modernists to a "loyal opposition" secretly nourished, by way of foundations and grants, by the bourgeoisie itself, while signally unconvincing, is surely itself enabled by the contradictions of the cultural politics of modernism proper, whose negations depend on the persistence of what they repudiate and entertain -- when they do not (very rarely indeed, as in Brecht) attain some genuine political selfconsciousness -- a symbiotic relationship with capital.

It is, however, easier to understand Kramer's move here when the political project of The New Criterion is clarified; for the mission of the journal is clearly to eradicate the sixties itself and what remains of its legacy, to consign that whole period to the kind of oblivion which the fifties was able to devise for the thirties, or the twenties for the rich political culture of the pre-World War I era. The New Criterion therefore inscribes itself in the effort, ongoing and at work everywhere today, to construct some new conservative cultural counterrevolution, whose terms range from the aesthetic to the ultimate defense of the family and religion. It is therefore paradoxical that this essentially political project should explicitly deplore the omnipresence of politics in contemporary culture -- an infection largely spread during the sixties but which Kramer holds responsible for the moral imbecility of the Postmodernism of our own period.

These positions -- antimodern, propostmodern -- then find their opposite number and structural inversion in a group of counterstatements whose aim is to discredit the shoddiness and irresponsibility of the postmodern in general by way of a reaffirmation of the authentic impulse of a high-modernist tradition still considered to be alive and vital. Hilton Kramer's twin manifestos in the inaugural issue of his journal, The New Criterion, articulate these views with force, contrasting the moral responsibility of the "masterpieces" and monuments of classical modernism with the fundamental irresponsibility and superficiality of a Postmodernism associated with camp and the "facetiousness" of which Wolfe's style is a ripe and obvious example.

What is more paradoxical is that politically Wolfe and Kramer have much in common; and there would seem to be a certain inconsistency in the way in which Kramer must seek to eradicate from the "high seriousness" of the classics of the modern their fundamentally anti-middleclass stance and the protopolitical passion which informs the repudiation, by the great modernists, of Victorian taboos and family life, of commodification, and of the increasing asphyxiation of a desacralizing capitalism, from Ibsen to Lawrence, from Van Gogh to Jackson Pollack. Kramer's ingenious attempt to assimilate this ostensibly antibourgeois stance of the great modernists to a "loyal opposition" secretly nourished, by way of foundations and grants, by the bourgeoisie itself, while signally unconvincing, is surely itself enabled by the contradictions of the cultural politics of modernism proper, whose negations depend on the persistence of what they repudiate and entertain -- when they do not (very rarely indeed, as in Brecht) attain some genuine political selfconsciousness -- a symbiotic relationship with capital.

It is, however, easier to understand Kramer's move here when the political project of The New Criterion is clarified; for the mission of the journal is clearly to eradicate the sixties itself and what remains of its legacy, to consign that whole period to the kind of oblivion which the fifties was able to devise for the thirties, or the twenties for the rich political culture of the pre-World War I era. The New Criterion therefore inscribes itself in the effort, ongoing and at work everywhere today, to construct some new conservative cultural counterrevolution, whose terms range from the aesthetic to the ultimate defense of the family and religion. It is therefore paradoxical that this essentially political project should explicitly deplore the omnipresence of politics in contemporary culture -- an infection largely spread during the sixties but which Kramer holds responsible for the moral imbecility of the Postmodernism of our own period.

Source type: picture

Source type: pictureInfo: The New Criterion was founded in 1982 by The New York Times art critic Hilton Kramer

Original size: 1024x978 px. Edit

Log-in

Log-in Source type: picture

Source type: picture