39

Hyatt Regencies

Author: John Portman

Year: 1967 Edit Add

Book: Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism

Hyatt Regencies

Author: John PortmanYear: 1967 Edit Add

Book: Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism

The building whose features I will very rapidly enumerate is the Westin Bonaventure Hotel, built in the new Los Angeles downtown by the architect and developer John Portman, whose other works include the various Hyatt Regencies, the Peachtree Center in Atlanta, and the Renaissance Center in Detroit.

The building whose features I will very rapidly enumerate is the Westin Bonaventure Hotel, built in the new Los Angeles downtown by the architect and developer John Portman, whose other works include the various Hyatt Regencies, the Peachtree Center in Atlanta, and the Renaissance Center in Detroit.

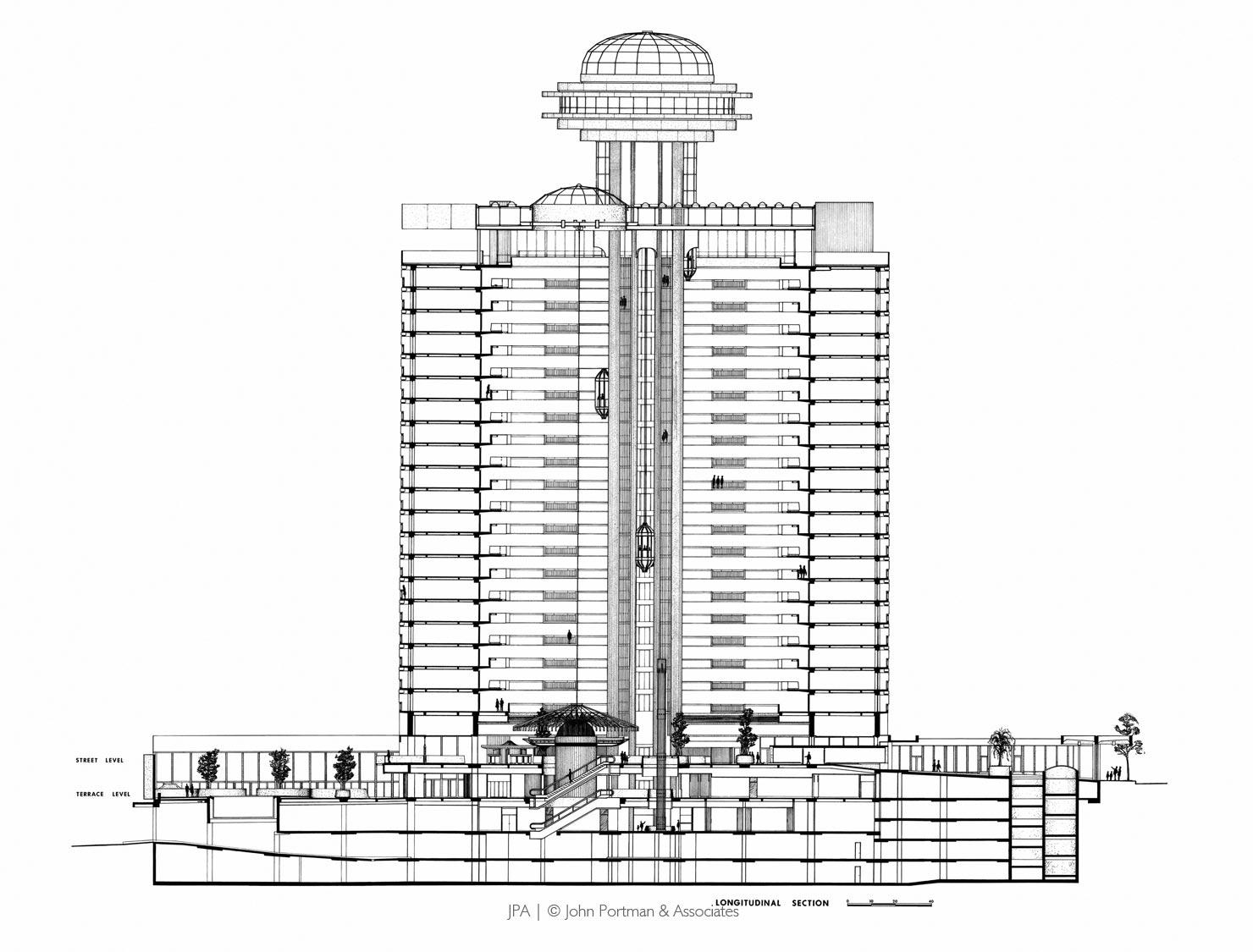

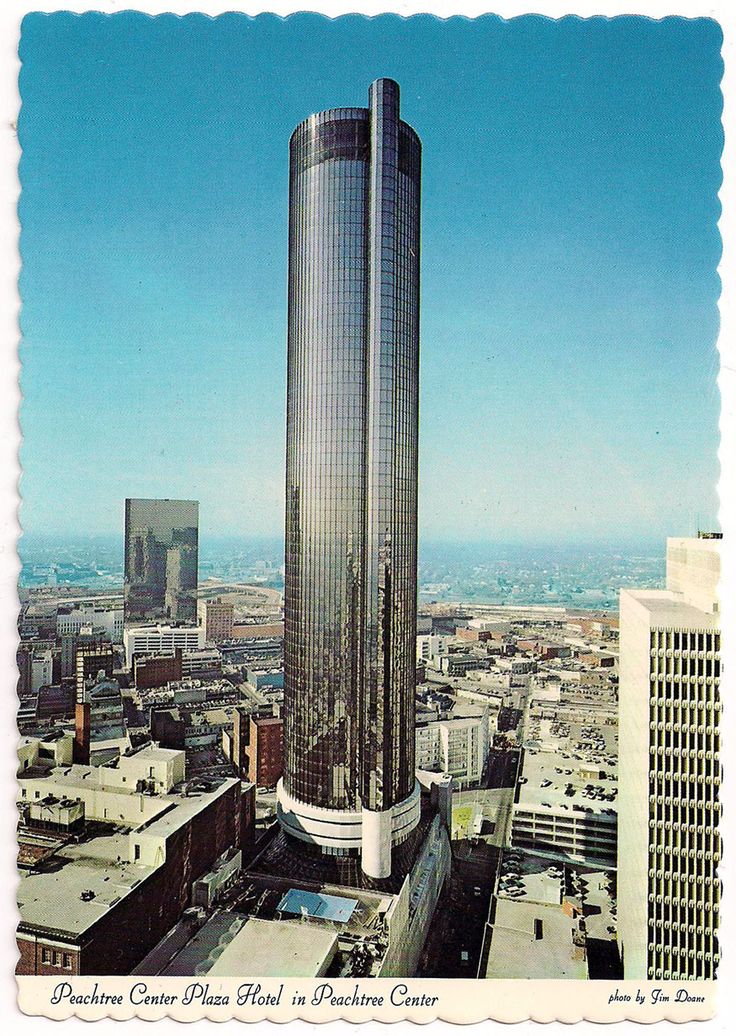

Peachtree Center

Author: John Portman

Year: 1965 Edit Add

Book: Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism

Peachtree Center

Author: John PortmanYear: 1965 Edit Add

Book: Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism

The building whose features I will very rapidly enumerate is the Westin Bonaventure Hotel, built in the new Los Angeles downtown by the architect and developer John Portman, whose other works include the various Hyatt Regencies, the Peachtree Center in Atlanta, and the Renaissance Center in Detroit

The building whose features I will very rapidly enumerate is the Westin Bonaventure Hotel, built in the new Los Angeles downtown by the architect and developer John Portman, whose other works include the various Hyatt Regencies, the Peachtree Center in Atlanta, and the Renaissance Center in Detroit

Source type: picture

Source type: pictureInfo: Portman with model of Peachtree Center, Atlanta

Original size: 2661x4086 px. Edit

Renaissance Center

Author: John Portman

Year: 1973 Edit Add

Book: Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism

Renaissance Center

Author: John PortmanYear: 1973 Edit Add

Book: Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism

The building whose features I will very rapidly enumerate is the Westin Bonaventure Hotel, built in the new Los Angeles downtown by the architect and developer John Portman, whose other works include the various Hyatt Regencies, the Peachtree Center in Atlanta, and the Renaissance Center in Detroit

The building whose features I will very rapidly enumerate is the Westin Bonaventure Hotel, built in the new Los Angeles downtown by the architect and developer John Portman, whose other works include the various Hyatt Regencies, the Peachtree Center in Atlanta, and the Renaissance Center in Detroit

Source type: picture

Source type: pictureInfo: Detroit Renaissance Center January 26 1976

Original size: 750x502 px. Edit

Source type: picture

Source type: pictureInfo: The Renaissance Center with Amtrack railroad cars. Circa 1980s.

Original size: 550x548 px. Edit

Source type: picture

Source type: pictureInfo: The Renaissance Center with Amtrack railroad cars. Circa 1980s.

Original size: 1218x1200 px. Edit

Westin Bonaventure Hotel

Author: John Portman

Year: 1976 Edit Add

Book: Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism

Westin Bonaventure Hotel

Author: John PortmanYear: 1976 Edit Add

Book: Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism

I have mentioned the populist aspect of the rhetorical defense of

Postmodernism against the elite (and Utopian) austerities of the great architectural modernisms: it is generally affirmed, in other words, that these newer buildings are popular works, on the one hand, and that they respect the vernacular of the American city fabric, on the other; that is to say, they no longer attempt, as did the masterworks and monuments of high modernism, to insert a different, a distinct, an elevated, a new Utopian language into the tawdry and commercial sign system of the surrounding city, but rather they seek to speak that very language, using its lexicon and syntax as that has been emblematically "learned from Las Vegas."

On the first of these counts Portman's Bonaventure fully confirms the claim: it is a popular building, visited with enthusiasm by locals and tourists alike (although Portman's other buildings are even more successful in this respect). The populist insertion into the city fabric is, however, another matter, and it is with this that we will begin. There are three entrances to the Bonaventure, one from Figueroa and the other two by way of elevated gardens on the other side of the hotel, which is built into the remaining slope of the former Bunker Hill. None of these is anything like the old hotel marquee, or the monumental porte cochere with which the sumptuous buildings of yesteryear were wont to stage your passage from city street to the interior. The entryways of the Bonaventure are, as it were, lateral and rather backdoor affairs: the gardens in the back admit you to the sixth floor of the towers, and even there you must walk down one flight to find the elevator by which you gain access to the lobby. Meanwhile, what one is still tempted to think of as the front entry, on Figueroa, admits you, baggage and all, onto the secondstory shopping balcony, from which you must take an escalator down to the main registration desk. What I first want to suggest about these curiously unmarked ways in is that they seem to have been imposed by some new category of closure governing the inner space of the hotel itself (and this over and above the material constraints under which Portman had to work).

I have mentioned the populist aspect of the rhetorical defense of

Postmodernism against the elite (and Utopian) austerities of the great architectural modernisms: it is generally affirmed, in other words, that these newer buildings are popular works, on the one hand, and that they respect the vernacular of the American city fabric, on the other; that is to say, they no longer attempt, as did the masterworks and monuments of high modernism, to insert a different, a distinct, an elevated, a new Utopian language into the tawdry and commercial sign system of the surrounding city, but rather they seek to speak that very language, using its lexicon and syntax as that has been emblematically "learned from Las Vegas."

On the first of these counts Portman's Bonaventure fully confirms the claim: it is a popular building, visited with enthusiasm by locals and tourists alike (although Portman's other buildings are even more successful in this respect). The populist insertion into the city fabric is, however, another matter, and it is with this that we will begin. There are three entrances to the Bonaventure, one from Figueroa and the other two by way of elevated gardens on the other side of the hotel, which is built into the remaining slope of the former Bunker Hill. None of these is anything like the old hotel marquee, or the monumental porte cochere with which the sumptuous buildings of yesteryear were wont to stage your passage from city street to the interior. The entryways of the Bonaventure are, as it were, lateral and rather backdoor affairs: the gardens in the back admit you to the sixth floor of the towers, and even there you must walk down one flight to find the elevator by which you gain access to the lobby. Meanwhile, what one is still tempted to think of as the front entry, on Figueroa, admits you, baggage and all, onto the secondstory shopping balcony, from which you must take an escalator down to the main registration desk. What I first want to suggest about these curiously unmarked ways in is that they seem to have been imposed by some new category of closure governing the inner space of the hotel itself (and this over and above the material constraints under which Portman had to work).

Log-in

Log-in Source type: picture

Source type: picture Source type: picture

Source type: picture Source type: picture

Source type: picture Source type: picture

Source type: picture Source type: picture

Source type: picture Source type: picture

Source type: picture Source type: picture

Source type: picture Source type: picture

Source type: picture